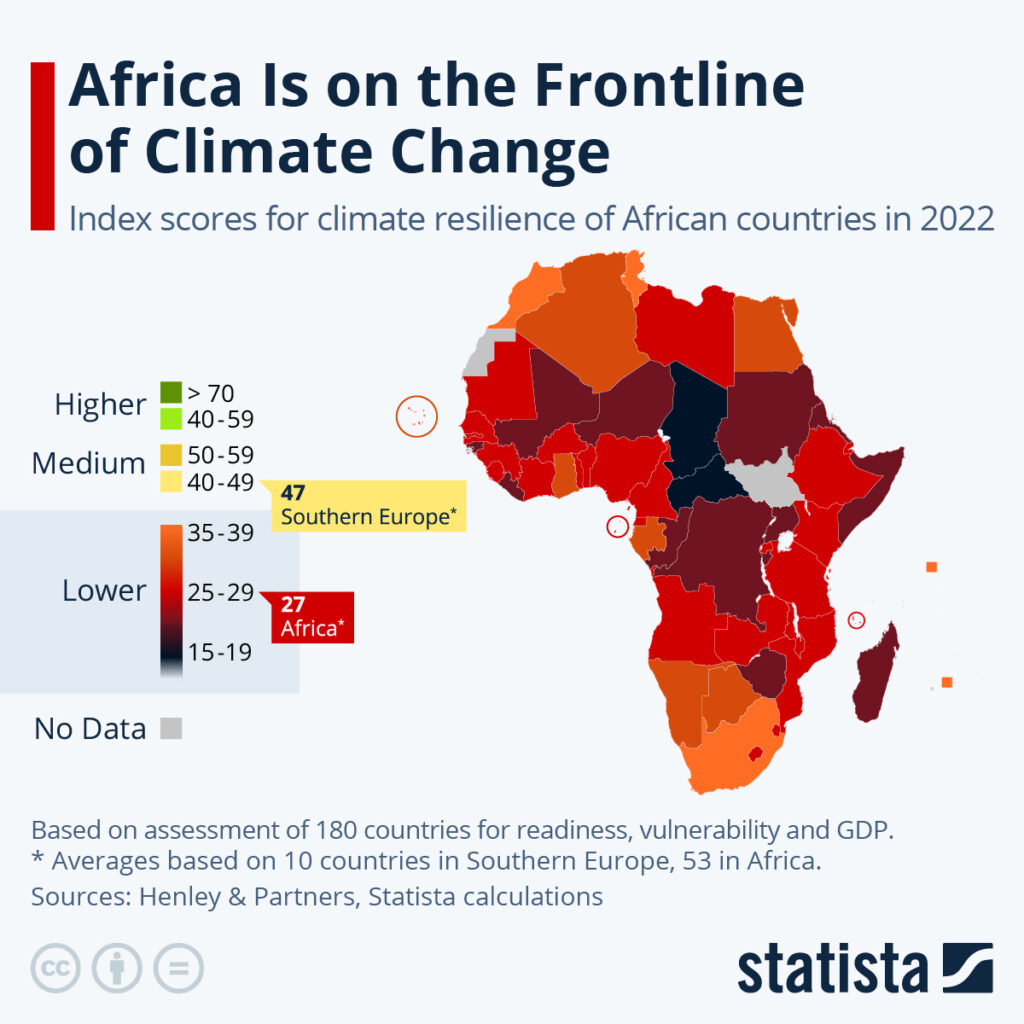

Africa is at the frontline of the global climate crisis, enduring some of its most devastating impacts while contributing less than 4% to global greenhouse gas emissions (IEA, 2022). From recurring droughts to deadly floods and heatwaves, the continent faces a multidimensional climate emergency that cuts across health, agriculture, water, and economic systems. While much of the world sees climate change as a looming future threat, for millions of Africans, it is already a daily life-or-death challenge. The crisis is escalating rapidly, driven by global inaction, financial inequality, and inadequate infrastructure. Africa’s ecosystems are collapsing, livelihoods are vanishing, and millions are being forced to migrate. The crisis is not only humanitarian but deeply environmental and economic. It undermines decades of development and threatens to undo hard-won progress on poverty reduction. From Sahel to the Horn of Africa, entire regions are now in prolonged emergency states. Urgent and equitable international support is not optional it is morally and globally essential.

Source: Statista 2022

Worsening Hunger and Food Insecurity

Africa is in the grip of a hunger emergency of staggering scale. As of 2024, more than 295 million people across 53 African countries are experiencing crisis-level food insecurity (FAO, 2024). Climate-related shocks such as prolonged droughts, erratic rainfall, and failed harvests are key drivers of this crisis. In Nigeria alone, 31 million people are affected by food shortages (IPC, 2024), while in the Sahel region, 45,000 people are on the brink of famine 42,000 in Burkina Faso and 2,500 in Mali (WFP, 2024). Climate extremes damage crops, reduce soil fertility, and kill livestock. Combined with conflict and economic hardship, climate stress pushes vulnerable communities into hunger traps. Food prices are rising, and supply chains are increasingly disrupted. Children, pregnant women, and the elderly are the most affected. The crisis is especially acute in areas dependent on rain-fed agriculture, which is failing under changing weather conditions. Hunger in Africa is no longer seasonal it is structural and chronic.

Severe Water Insecurity and Droughts

Water scarcity is reaching alarming levels in Africa, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions. As of 2024, around 116 million people across eight African countries do not have access to safe drinking water (UNICEF/WHO, 2024). The rapid pace of global warming is disrupting rainfall patterns, reducing snowmelt, and accelerating evaporation from lakes and rivers. Lake Chad, once one of Africa’s largest freshwater bodies, has shrunk by more than 90% since the 1960s, impacting 30 million people in Nigeria, Chad, Cameroon, and Niger (UNDP, 2021). Projections suggest that by 2025, up to 460 million people in Africa could live in water-stressed regions (UNEP, 2022). Farmers and herders are clashing over dwindling water sources. Women and girls often walk miles to find water, losing time for education or income-generating activities. Waterborne diseases are also increasing as contaminated supplies become common. The lack of water is intensifying migration and exacerbating tensions. Droughts are no longer rare they are becoming permanent features of African life.

Floods, Storms, and Climate Disasters

While some regions suffer drought, others are overwhelmed by floods and storms. In 2024 alone, 27 African countries experienced severe flooding that killed over 2,500 people and displaced nearly 4 million (IFRC, 2024). South Sudan was among the worst affected, with 735,000 people impacted and 65,000 displaced from their homes (UNOCHA, 2024). In Somalia, flash floods swept through Mogadishu, leaving 200 families homeless (IOM, 2024). These floods destroy homes, roads, and farmland, contaminating drinking water and spreading cholera and other waterborne diseases. They also displace entire communities, many of whom lack the resources to rebuild. Africa’s flood vulnerability is worsened by poor urban planning, deforestation, and lack of drainage infrastructure. With climate change intensifying, rainfall is becoming more erratic and intense, overwhelming systems that are already fragile. The frequency of such disasters is rising, leaving no time for recovery between shocks. This is a disaster cycle that threatens to trap millions in poverty.

Economic Damage and Development Setbacks

Climate change is inflicting massive economic losses across Africa. According to the World Meteorological Organization, African countries lose 2% to 5% of their GDP annually due to climate-related shocks (WMO, 2022). These include damages from drought, flooding, lost agricultural productivity, health crises, and migration. Adaptation costs are enormous: Sub-Saharan Africa alone will need $30–$50 billion annually through 2030 to build resilience (AfDB, 2023). Without intervention, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) warns Africa could suffer a 7.1% drop in GDP per capita by the century’s end (IMF, 2023). Climate disasters disrupt trade, deter foreign investment, and increase public spending on relief and infrastructure repair. For smallholder farmers, one bad season can mean bankruptcy. Insurance markets are underdeveloped, leaving people vulnerable to total loss. As economic growth slows, unemployment and inflation rise. Without climate-smart development, Africa risks long-term stagnation. The cost of inaction will far exceed the cost of investment.

Health Systems Under Climate Stress

Africa’s health systems are collapsing under the weight of climate-linked illnesses and malnutrition. In 2024, 38 million children under five were acutely malnourished (UNICEF, 2024). Rising temperatures and changing ecosystems are expanding the reach of vector-borne diseases like malaria and dengue fever (WHO, 2023). Heatwaves are causing increased maternal complications such as pre-eclampsia and gestational diabetes (Lancet, 2023). Waterborne diseases like cholera are spiking in flood-hit zones. Climate anxiety and trauma are also fueling mental health crises, particularly among youth and displaced populations (WHO Africa, 2023). Health facilities often lack reliable power, clean water, or climate-proof infrastructure. This makes it harder to deliver services during emergencies. Women and children, already at risk, face increased exposure to disease and violence. Without investment in resilient health infrastructure, more lives will be lost each year. Climate change is becoming the single biggest threat to public health across Africa.

Agricultural Collapse and Rising Import Dependency

Agriculture, the backbone of most African economies, is disintegrating under climate pressure. Since 1961, African agricultural productivity has declined by 34%, the largest regional drop globally (IPCC, 2022). Crop yields are falling due to heatwaves, changing rainfall, and pests, while livestock deaths are rising from heat stress and lack of grazing land. Farmers face unpredictable growing seasons and increasingly unreliable harvests. As a result, food imports are projected to skyrocket from $35 billion today to $110 billion annually by 2025 (AfDB, 2022). This import dependency threatens food sovereignty and increases national debt. Smallholder farmers, who feed most of the continent, are the hardest hit. With limited access to irrigation, finance, or climate-resilient seeds, their livelihoods are collapsing. Without investment in sustainable agriculture, food crises will worsen. The sector urgently needs innovation, infrastructure, and financing to survive.

Climate Finance Deficit and Broken Promises

The gap between climate finance commitments and delivery remains wide. Africa received $43.7 billion in climate finance in 2021/22, a 48% increase over previous years but still far short of the $277 billion per year it needs (CPI, 2023; AfDB, 2023). If current trends continue, the continent faces a $2.5 trillion gap by 2030 (UNEP, 2023). Despite repeated promises at COP summits, much of the funding from developed countries has been delayed, rerouted, or insufficient. Without climate finance, African countries cannot invest in renewable energy, early warning systems, or infrastructure adaptation. The lack of funds also limits disaster recovery, education, and health efforts. Climate finance must be grant based, accessible, and directed toward those most vulnerable. Climate justice requires more than talk it demands transfer of resources and technology. The future of millions hangs on global financial equity.

Africa’s Warming Climate and Cyclone Threats

Africa is warming faster than much of the rest of the world at a rate of +0.3°C per decade, slightly above the global average (WMO, 2022). The Horn of Africa has endured five consecutive failed rainy seasons, the worst drought in 40 years (FAO, 2023). Meanwhile, tropical cyclones have grown more intense and destructive, ravaging countries like Mozambique, Malawi, and Madagascar (UNOCHA, 2023). The combination of drought and storm leaves communities trapped between two extremes. Dry conditions destroy crops, while storms wipe out infrastructure. Warming temperatures are altering ecological balances, threatening species extinction and biodiversity loss. Forests are burning, wetlands are shrinking, and ecosystems are degrading. These changes further reduce Africa’s ability to adapt. Unless warming is slowed globally, many African regions may become uninhabitable. The science is clear climate change is escalating faster than previously predicted.

Oceans, Fisheries, and Coastal Collapse

Africa’s oceans and fisheries are under siege. Over 200 million Africans rely on fish as their primary source of protein (FAO, 2022). However, with 1.5°C of global warming, marine fish catch potential could fall by 41%, and by 69% at 4.3°C (IPCC, 2022). This threatens both food security and millions of livelihoods in coastal communities. Rising sea temperatures and ocean acidification are already shifting fish populations away from traditional fishing zones. Coral reefs are bleaching, mangroves are vanishing, and breeding grounds are disappearing. In West Africa and along the Indian Ocean, small-scale fishers are losing their incomes. Overfishing by foreign fleets further exacerbates the crisis. Coastal tourism and trade, crucial to economies like Seychelles and Mauritius, are also at risk. Without urgent marine protection and policy reform, this crisis could devastate the continent’s Blue Economy.

Rising Seas and Urban Risk

Sea-level rise poses an existential threat to Africa’s coastal cities. By 2030, up to 116 million people on the continent could be exposed to sea-level rise climbing to 245 million by 2060 (World Bank, 2021). Cities like Lagos, Alexandria, Dar es Salaam, and Abidjan face flooding, infrastructure collapse, and population displacement. Informal settlements, home to many urban poor, are often built in flood-prone zones without adequate drainage. Rising seas also endanger ports, energy infrastructure, and freshwater sources. Urban migration is accelerating, placing even more pressure on vulnerable cities. Without resilient urban planning, the social and economic fallout will be catastrophic. Coastal cities are both economic hubs and homes protecting them must be a top climate priority. Nature-based solutions like mangrove restoration can help, but funding and political will are critical.

Conclusion

Africa’s climate crisis is not a distant forecast it is a brutal, present-day emergency threatening lives, livelihoods, and the future of the continent. It is a crisis of hunger, water, displacement, disease, and collapsing economies, made worse by historic injustice and global neglect. Despite contributing the least to the problem, Africa bears a disproportionate share of the burden. The cost of inaction is already catastrophic and rising. Climate justice demands that wealthy nations honor their promises through financing, technology transfer, and solidarity. At the same time, African leadership must drive bold, climate-resilient development that protects people and ecosystems. Africa is not just a victim it is a frontline of resilience, innovation, and hope. The world must stand with Africa not in sympathy, but in partnership.

—————————————

By Abdishakur Daaha is the Founder and Director of the Climate Generation Movement and a distinguished Environmental and Agricultural Consultant with a proven track record in climate resilience, modern agriculture, and sustainable economic development.